TRANSCRIPTS

My Interview with Dr. Vinton Gray Cerf

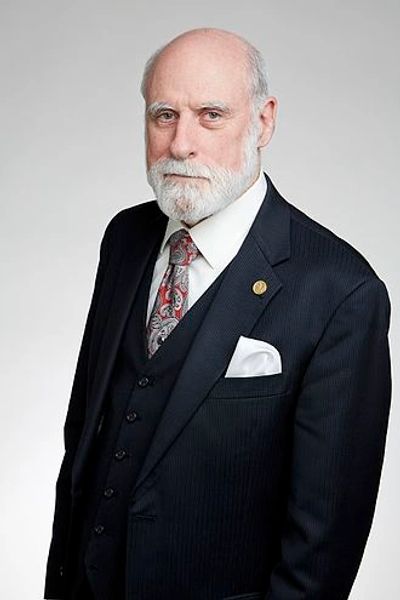

Bill Kozel: My guest this week is Dr. Vinton Gray Cerf, Vice President and Chief Internet Evangelist for Google. Welcome to TECHNYCAL, Vint.

Vinton Cerf: Thanks for having me on the show, Bill.

BK: At the Internet Society event I attended, you spoke passionately about the preservation of digital assets and about a digital dark age. We’re only one-fifth of the way through the 21st century, and it's only going to get worse as new standards are created. Why is it so important that we preserve these assets and what are the challenges?

VC: So, I'm amused by the term “Digital Dark Age” especially if you mispronounce it and say, “It's a Digital Dork Age.” We could have an entire conversation on either of those two interpretations.

But, let me stick with the dark age problem. My big worry is that we create a huge quantity now of digital content – whether it's our images that go up on Facebook or Snapchat or other – or the texts that we send each other or the blogs that we put up or the web pages that we manage – the social media, Twitter, for instance, among other. So, there's this huge amount of digital content that we collectively produce, and one of the interesting questions is – what is its long-term likelihood of being available?

I suspect that many people will say, “Well, most of it isn't worth anything, so it doesn't matter if it goes away.” On the other hand, you and I might think that at least some of what either we have generated or what we have encountered is important and valuable and worthy of preservation. The problem is, none of us has enough memory – literally, physical memory – in order to record and capture everything that we might think is valuable. And, in fact, we're misled into thinking it's all there all the time, because the Web feels like it's there all the time and that everything is there. It's there when you search for it until it isn't.

And it is this momentary shock of, “Oh my God. Page not found. What happened? Is the website gone? Is the data erased? And what am I gonna do if I was relying on that?”

From the academic point of view, it’s quite troublesome, because we publish papers now with URLs in them that are footnoted, for example, to bolster our views or analyses and the like, and if 10 or 15 or 20 or 100 years from now, someone reading our work is unable to find the corroborating documents because the web pages are gone, the URL, with its domain name is no longer in use, then we’ve actually harmed our descendants – our academic descendants – because they can’t get the data that corroborated our arguments.

So, it gets more exacerbated when you start thinking about scientific data – the data that we collect about the environment, data that we collect from the Rovers that are on Mars, or various telescopes that are either on planet Earth or in space.

Imagine all of that data and the metadata associated with it – the calibration data associated with the instruments – for some reason, is not adequately preserved. Well, now, we’ve lost important scientific information that we might have used to go back and perhaps re-confirm or confirm a new theory.

And historians, by the way, will also tell you that sometimes, you don't know that something is important until 100 or 200 years later or more, because it was a key communication – a particular policy position, an action that was taken – a private email that was exchanged – that might turn out to be the key to understanding something important that happened in history.

And then, to bring this home to ordinary users, think of all the photographs that we take with our mobiles. They often end up on the mobile. Sometimes they end up in the cloud. If you value those photographs – those images or videos – what is to guarantee that they will stay in the cloud? What if the cloud provider goes away? What if they decide, “This isn't a good business anymore?” What should you do?

So, we have many, many different reasons for being concerned about this. The digital records that we need for daily life – for example, transactions – real estate transactions, for instance, which should be recorded somewhere, our important documents like birth certificates, death certificates, marriage certificates, other important bona fides, like, our college degrees, our certificates of training – all of those often have a digital manifestation.

And, once again, if those things are not adequately preserved, what happens when you want to cite them in order to make an argument that you should be granted some permission to do something or you have the bona fides to undertake a project?

BK: Are there enough servers on Earth to store all that data?

VC: Well, you know, this is one of the questions about do we preserve everything. And I am not advocating that we should preserve everything. Even if Google wanted to, I don't think that it could. However, I think that there should be tools around that you can invoke if you thought something should be preserved. So, there is this capacity to preserve in the functional sense.

There's capacity to preserve in literally, the digital memory sense. And I am not advocating that we should remember everything, but I am saying that we should have the ability to preserve things that we all generally believe need to be preserved. Financial transactions or certainly, real estate transactions, intellectual property transactions have long-term significance, and have historical importance. So, same is true for patents, for example. Patent filings are extremely important.

So, we need to find a way to preserve those, and think about the National Archives here in the United States, which is supposed to capture the records of each presidential administration. They, too, are faced with this digital preservation problem, because they receive laptops and desktops or hard drives and so on, and they have to find a way to catalog them, to index them, to capture the content and understand which software is needed in order to read the documents. Is this a Microsoft Word document? Is it a PDF? Is it a spreadsheet? Is it something else? Which is an intensely difficult thing to do, because the vintages of the various devices that are used in government will vary over time. The software will vary over time. And yet, the archive has to be able to extract and retain utility of that information.

BK: You’ve been Google’s Chief Internet Evangelist since 2005. What are your goals for 2018?

VC: Well, I can tell you the ones that I am most concerned about. The first is – continued spread of the Internet. It’s something I would like very much to promote. We are at about 50 percent of the world’s population right now, and we have, again, another 3.7 billion people to go. So, that’s very high on my priority list.

Second thing, we just talked about, which is preservation of digital content and finding technical ways to do that. Finding business models that will sustain preservation – and finding legal regimes, for example, that would allow a library or an archive to have the right to hold the content – including software, which it might then need to execute on behalf of a third party in order to render or allow interaction with a particular digital object – for example, a spreadsheet.

So, the digital preservation is very high on my agenda for 2018. The third thing which is very high on my agenda is trying to cope with many deficiencies in security and safety that we are encountering in the online environment. This is exacerbated by the avalanche of devices – the so-called Internet of Things, that may become part of the Internet landscape – containing software which has not necessarily been well thought out or hasn’t been configured for maximum safety and security.

I’m very worried about malfunctions, about misconfigurations, about inappropriate access control – either invading privacy or actually interfering with operations. So, that’s a huge, really complex space. So, IoT is on my list of important things to worry about.

And finally, as we all recognize, the difficulties of retaining privacy in the online environment. How should we try to cope with that as everyone runs around with their high-resolution cameras taking pictures of everything and uploading them and sharing them?

That concern expands into the broader question of safety and security, defense against malware, defense against denial of service attacks, invasion of privacy, identity theft, fraud – all kinds of abuse – whether that’s harassment or child pornography or other kinds of abuses that we often encounter.

The one hard question is what to do about all that, particularly the international setting. What kinds of cooperation might we look for across international boundaries? To what extent can we outfit the user population with means to defend themselves against these various harmful possibilities – including providing them with two-factor authentication and other strong ways of inhibiting hijacking on someone’s account.

So we have to teach people digital literacy from an early age and help them feel both comfortable and motivated to exercise their digital literate skills to protect themselves from various kinds of risk and potential attack.

So, my goodness – and that's just the first four things or five things on the list, and much – there’s much more. I’ll add one more, just because it’s such a tasty thing, and that’s the continued evolution of the interplanetary Internet.

BK: That's what I was going to ask you about next.

VC: We are, at the moment, in the middle of a study for NASA – Google is not doing this; this is a NASA-wide effort – to look at what it would mean to deploy a distribution tolerant networking protocol – a bundled protocol – on all new spacecraft and, of course, some already existing ones in order to improve our ability to support demand in robotic space exploration as we explore the rest of the solar system. So, that, too, is on my list of things to attack this year.

BK: That segues nicely into my Internet of Things question. How long do you think it will be before we have uniform standards for the Internet of Things?

VC: Well, I think that we could probably anticipate that there will be lots of standards, and that’s the problem. There will be too many of them. So, coming to some sort of, I would say, a coherence in the Internet of Things standard space is gonna take time. It will be partly a matter of technology and partly, frankly, a matter of tipping points where some particular product becomes more popular than the others and becomes the sort of poster child for a particular set of protocols.

I’m guessing that we're talking about five years before we would see this sort of settle down, because there’s an awful lot of unknown issues arising in this space, and I think we will literally have to live through some of the mistakes that people make and some of the protocol deficiencies that we encounter before we have a better sense, anyway – if not the best sense – of what protocols ought we to standardized and then make reinforceable with regard to safety and security and reliability.

BK: We recently had a conversation with NVIDIA’s Ian Buck about deep learning in neural networks. Where do you see those technologies in the next five to 10 years?

VC: Well, I would say that we are on quite a tear right now, generally, with regard to machine learning. This is triggered largely by having very large scale, multilayer neural networks that can be trained to do very complex and sophisticated things.

Despite the sophistication, though, it’s still – the applications that are the most spectacular are quite narrow. Playing Go is quite impressive, and Alpha Zero, which learned how to play Go in a few days’ time, and that it was playing at grandmaster level is quite stunning. On the other hand, it’s easy to point out things that a two-year-old child can do that no programs are able to do.

So, we have a long ways to go in terms of general intelligence exhibited by these systems – not just multilayer neural networks, but possibly others as well. On the other hand, I am confident that we're going to see a large number of narrowly based functions subject to machine learning.

So, for example, some control systems are really good candidates for this kind of training. In our case, in our data centers, we have a cooling system, which is essentially managed by pumps and my opening and closing valves and choosing pump speeds and things like that. And it cost us a certain amount of money to cool the data center, because we consume power to run the pumps and so on. And we discovered that by applying machine learning, that we can reduce the cost of the power needed to run the pumps to cool the system by a factor of 40 percent.

BK: Wow.

VC: Yeah. That was my reaction, too. It was just plain, “Wow.” So, there’s a good example of an optimizable thing. It’s very, very clear, optimum criterion, which is reduce the amount of power required to cool the data center.

So, that propagates back up into the neural network. So these are the kinds of applications I’m anticipating. I’m not really expecting a lot of general purpose intelligence, though, to come to the fore – at least not in the short term.

BK: At the Internet Society event you also said, “I'm just a humble programmer,” which got a big laugh. You’ve written about responsible programming. What do you mean by that?

VC: Oh, thank you. That’s a very important question. I think that the programmers have an ethical responsibility to be extremely thoughtful about the code that they write and the dependence that people will have on it. It’s particularly true, of course, in self-driving cars and robotic medical instruments and things like that, but I think it's just as true for the thermostat as it is for the da Vinci robot – operational robot.

BK: The surgical robot.

VC: Yes – Intuitive Surgical, I think, is the company that makes it. I think all of us who make a living writing software, have this ethical responsibility to be very thoughtful about who is depending on this stuff. What happens if it doesn't work right? What can I do to avoid making stupid mistakes?

How can I detect those mistakes if I have made them? How do I update the software? How do I make sure that the device receiving new software is not receiving malware from some improper source? All of those concerns are on the table, and I think we still have a lot of work to do to put incentives in place that will cause companies to adopt practices that would produce the desired result, which is better quality software.

BK: So what else are you interested in? Music, theater, sports, geology, et cetera?

VC: Well, let's see. I am not a sports person. I’m embarrassingly ignorant. And so, if somebody names a team, I won't really know if it’s a basketball team or a football team or something else. I am a classical music fan. I tend not to listen to anything composed after 1850.

I am a newly and deeply interested in cell microbiology – microchemical behavior or processes in cells. Not that I’m an expert, but because I am so fascinated with the way cells work, it’s incredibly complex. And the result is that I’ve become fascinated by how cells work and, particularly, how they don’t work. And without going into a long monologue, cells normally are programmed to live for a certain period of time, to reproduce a number of times, and then, essentially, commit suicide. It’s called cell apoptosis.

Some of the cells don’t do that. Some of them continue to reproduce ad infinitium – we call that cancer. Others don’t die, and they aren't cancerous, but they start cranking out toxins, and we call those – well, I call them grumpy old cells, but there is a medical term for a cell which has reached this sentient state where it’s senile, almost. Still alive, not reproducing, but producing toxic chemicals that harm your body. So, all of that is of great interest to me, especially as I get older.

So, I’m finding myself digging deep into what is known and what is not known about nuclear cells or eukaryote cells.

BK: So even your hobbies are complex.

VC: Well, I also love good wine and good food, and so, I’m a happy collector and consumer of wines. I don’t collect the wines to resell them. I collect them to drink them. So, I keep that in mind when I acquire a bottle.

BK: And finally, if you’re not tired of talking about it, could you please tell us about the development of the Internet protocol and your work for you DARPA? If you don't want to, you don't have to.

VC: No, no, it’s fine. Well, first, it should be understood that I’m not the only person who is involved in this. Bob Kahn started the Internet protocol development work in ‘73, but Steve Crocker deserves credit – and several others – for developing the predecessor host-to-host protocol for the ARPANET [Advanced Research Projects Administration], for example. And then, of course, as the Internet project unfolded, I went from running my bit of it at Stanford to running the entire program at DARPA [Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency] starting in 1976.

Many, many hands have touched these protocols or invented new ones and it’s a tribute, I think, to the institutions that were invented – the International Network Working Group, the Internet Architecture Board, the Internet Engineering Task Force, the Internet Research Task Force – these institutions plus the Internet Society and ICANN and the regional Internet registries and so on were all created at need, and the protocols were permitted to be invented or adapted because the architecture was so open. And the philosophy was to open to contributions from others.

And so, if there’s this huge success to be cited here, I think it is that the network continues to be a very open, technical environment where new ideas are welcome.

BK: So, what is the software that runs Vint Cerf?

VC: [Laughs] Well, it’s “Wetware,” and all I can say is that I have a dose of DNA and it seems to have in it a great dose of curiosity, a desire not to grow up. Getting older is inescapable but growing up is optional – to borrow somebody else’s quote.

I live a very, very privileged life, one which allows me all kinds of opportunities to learn new things and encounter new ideas, and I really live for that. I think the world would be pretty boring if you knew everything there was to know. Right now, I know I know hardly anything that there is to know, and so I’m not worried about running out of new things to learn.

BK: My guest has been Vint Cerf, Vice President and Chief Internet Evangelist for Google. Thanks so much for being here, Vint.

VC: Thanks, Bill. I enjoyed the chat.

Copyright © 2019 TECHNYCAL - All Rights Reserved.